OXFORD, Miss.—In Drunktown, death is as everyday as the horn blasts of the trains running through the heart of it, the drinkers who populate Eddie’s and its other watering holes, and the trucks that motor in from the desert and back out again. Flashes of love, beauty and sensuality ease the trauma and grief, but sometimes also become part of it.

“Your cheekbone cold against my face,

a whirring rock marrow deep.”

Such are the images in the poetry of Jake Skeets, the John and Renée Grisham Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi. The 33-year-old Navajo poet sat down with me recently at Heartbreak Coffee just off Oxford’s Square. He talked about those images and the city that inspired many of them—Gallup, N.M., the “Indian Capital of the World,” also known as “Drunktown” in Skeets’ world.

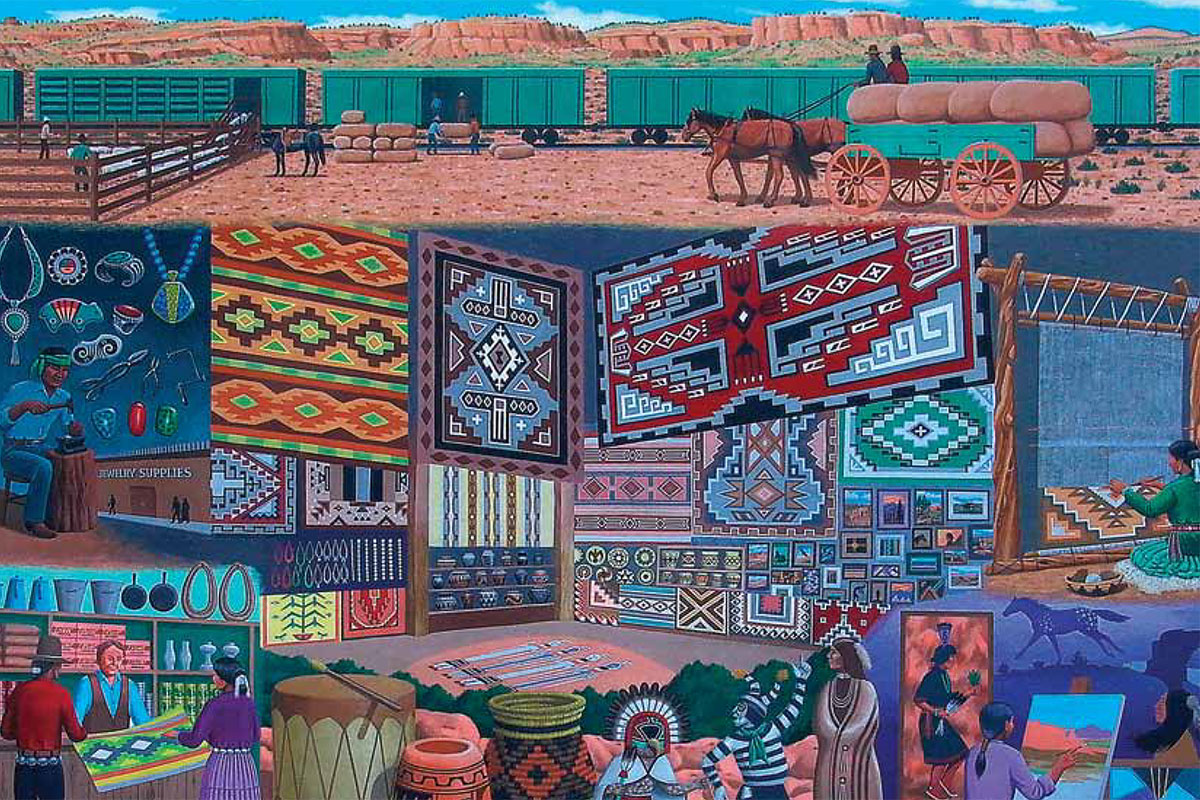

“It is very much a point of beginning,” Skeets explained. “I grew up just south of Gallup. Gallup is situated on Route 66, on the railroad, a town that exists because of the expansion of the West. … It sits at the intersection of my life and all the Native Nations around it: the Navajo, the Hopi, Laguna, Zuni.”

Trains haunt Skeets’ poetry. The tracks that carry the trains are too often the place where lives end, whether they’re drunken stumblers from the bars or the suicidal who’ve given up on life.

“intestines blown into dropseed

strewn buffalograss blood clots

eyes bottle dark

mouth stuffed with cholla flower.”

These are lines from the title poem in Skeets’ 2019 book of poetry, “Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers,” a winner of the National Poetry Series. The poem is the tale of a young boy’s suicide, a major problem in the Native American community.

It is one of many problems in the Navajo Nation, which includes a reservation the size of West Virginia and parts of Utah, New Mexico and Arizona. Thousands of families there live without electricity and running water. The unemployment rate is 50%. Half of all adult Navajos suffer from Type 2 diabetes. Their mortality rate is more than 30% higher than that of the rest of the nation. With such poverty come the usual ills—drugs, domestic violence, crime and suicide.

| In this short film, Jake Skeets reads his poem, “Drunktown” as part of the online event “Songs at the Confluence: Indigenous Poets on Place,” produced in collaboration with Tippet Rise Art Center and In-Na-Po (Indigenous Nations’ Poets). Video courtesy the Adrian Brinkerhoff Poetry Foundation / Youtube |

Charcoal also figures in Skeets’ poetry as well as in Navajo culture. “When you want protection, you go through a ceremony that involves ash or charcoal. When we would go out at night, we put ash on our forehead. When we were kids and afraid to go in the dark, my mom would say, ‘Put ash on your forehead.’”

Sprinkled here and there in Skeets’ poetry is Diné, the Navajo language, a language with an intricate verb system and syntax much different than English. It is also imbued with the strong sense of community, rather than the individual, that characterizes Navajo thinking.

Skeets’ poetry even includes blank pages or pages with nothing more than a dash. The poet describes those pages as “breathing room,” where the reader can reflect and include his or her own feelings about the poem.

“With a lot of images of violence and death, it makes sense to have a space, to take a break. It is also very functional, utilitarian,” Skeets continues. “In Navajo, there is a belief that whatever design you have or create, you should have an escape point. In Navajo rugs you’ll have imperfection where the weaver was creating empty spaces or pockets. You don’t want to be trapped inside your creation.”

The Future of Navajo Poetry

Music is also important to Skeets and the Navajo in general. As he currently works on a novel set in the 1980s as well as more poetry and essays, Skeets said he is listening to a lot of music from the 1980s, including Black Sabbath, AC/DC, and Guns N’ Roses. “When I heard Black Sabbath for the first time, I was through the moon,” he said with a laugh.

His poetry rings with a kind of music as well. “Jake Skeets sings this reservation bordertown into being, where the ‘Navajo word for eye hardens/into … war,’” writes Navajo poet and American Book Award winner Sherwin Bitsui. “The future of Navajo poetry reveals itself in (Skeets’ book’s) pages.”

Masculinity is another Skeets theme. “I feel like we understand masculinity in a very physical sense. Our ideas are centered around destruction and overcoming. Intimacy is something that is opposite of that,” Skeets continues. “Intimacy is something connected to body, emotion, and desire. When you have the intersection of those two things, there is a singular movement where you can weigh in over intimacy or weigh in over to violence, and that is true everywhere.”

A striking feature of Skeets’ book “Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers,” is its cover, a photograph of Skeets’ late uncle Benson James. Taken in 1979 by famous photographer Richard Avedon, the photograph shows James as something of a mystery—a long-haired, inscrutable Navajo, eyes narrowed, lips pursed, in soiled working man clothes. A skilled mechanic, he would be murdered a year later.

“In my graduate program, you have to write a book. That is how you graduate. When I saw the portrait of Benson, that shifted everything,” Skeets said. His family “remembers him fondly as a protector, but he also had a very dark side.”

Skeets’ time in Mississippi comes to an end in May 2024. He told me that the tales of the South’s hospitality, its good food, and the riches of its culture have proven to be true. As a Native American with his people’s own tortured history, he can also appreciate Mississippi and the South’s ongoing efforts to reach a reconciliation with the past.

“I definitely do see those efforts of reconciliation while also honoring what has happened,” Skeets said. “Working through it is probably the most important, as long as you are willing to come to the table. This happened. How do I move forward? The easier choice is to remain ignorant.”

This MFP Voices essay does not necessarily represent the views of the Mississippi Free Press, its staff or board members. To submit an opinion for the MFP Voices section, send up to 1,200 words and sources fact-checking the included information to azia@mississippifreepress.org. We welcome a wide variety of viewpoints.